Biology's Longitude Problem

Biotech is the only trillion dollar industry that still feels oddly similar to pre-chronometer Renaissance navigation. We have beautiful instruments and brilliant crews, yet an alarming amount of educated guessing. When I came from engineering into biology, I didn't expect so much of the workflow to boil down to "squint and hope we're roughly here."

Long before GPS, sailors could measure "latitude" easily. A quick look at the sun or a star and they knew their north-south position with decent confidence. But "longitude" was a different story. There was no reliable way to know how far east or west you were.

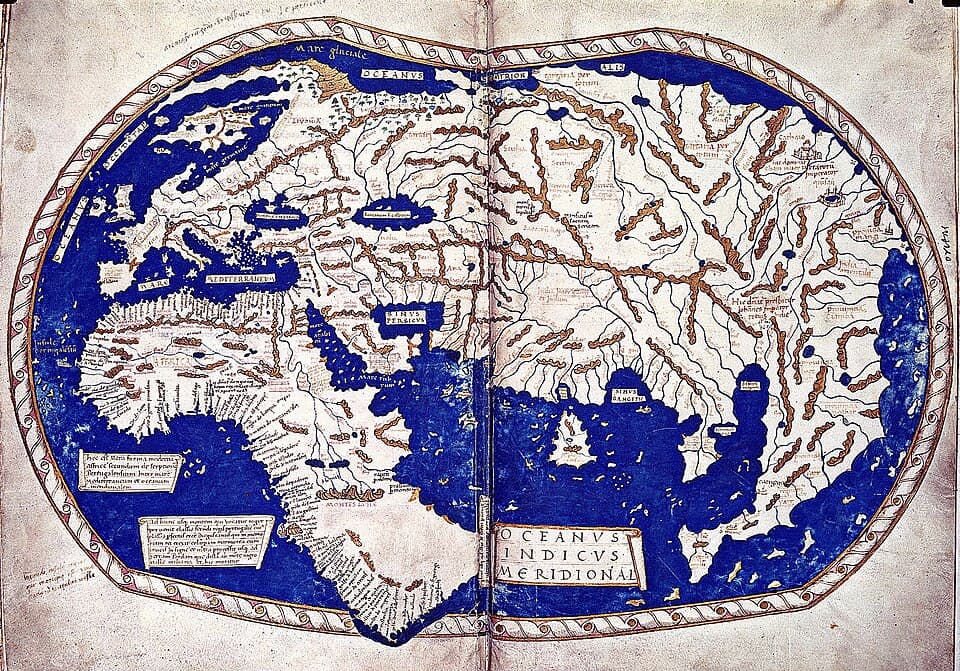

This gap is obvious in early world maps (e.g. from the Martellus Map (Figure 1) to numerous 15th–16th century charts) where coastlines are distorted, continents are misplaced, and many features were copied from "prior art" rather than empirical measurement. Sailors could follow a stable latitude across an ocean, which made long-distance voyages to India feasible centuries before modern instrumentation, but because no one could determine their actual east-west position, chronic drift was inevitable. It worked mostly well enough though… until it didn't. The 1707 Scilly disaster made this painfully clear: a British fleet misjudged longitude and wrecked four ships, killing ~2,000 sailors.

Source: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale.

For a long time, the prevailing belief was that better ships, improved seamanship, and more detailed coastal observations would solve these discrepancies. But none of these touched the core constraint: without a stable reference clock, longitude could not be computed. Finally, once John Harrison built a marine chronometer stable enough to keep accurate time at sea, longitude became measurable. And that was when navigation really became "engineerable" and now industries were built on top of it, world maps were redrawn, and trade exploded.

Modern biology feels uncomfortably close to that pre-chronometer period. We have extraordinary instrumentation and increasingly automated workflows, yet most discovery programs and so many of our conclusions depend on indirect proxies, partial readouts, and one-dimensional assays that approximate what's really happening inside cells. I've worked in labs where new robots were treated like miracle cures. More steel, more arms, everything looks futuristic except that it still operates the medieval map. One receptor. One construct. One plate. Some screens ran for five or six months, producing datasets so specific to a single question that by the time the results arrived, the entire workflow had been inadvertently over-fitted to that assay.

Ref.

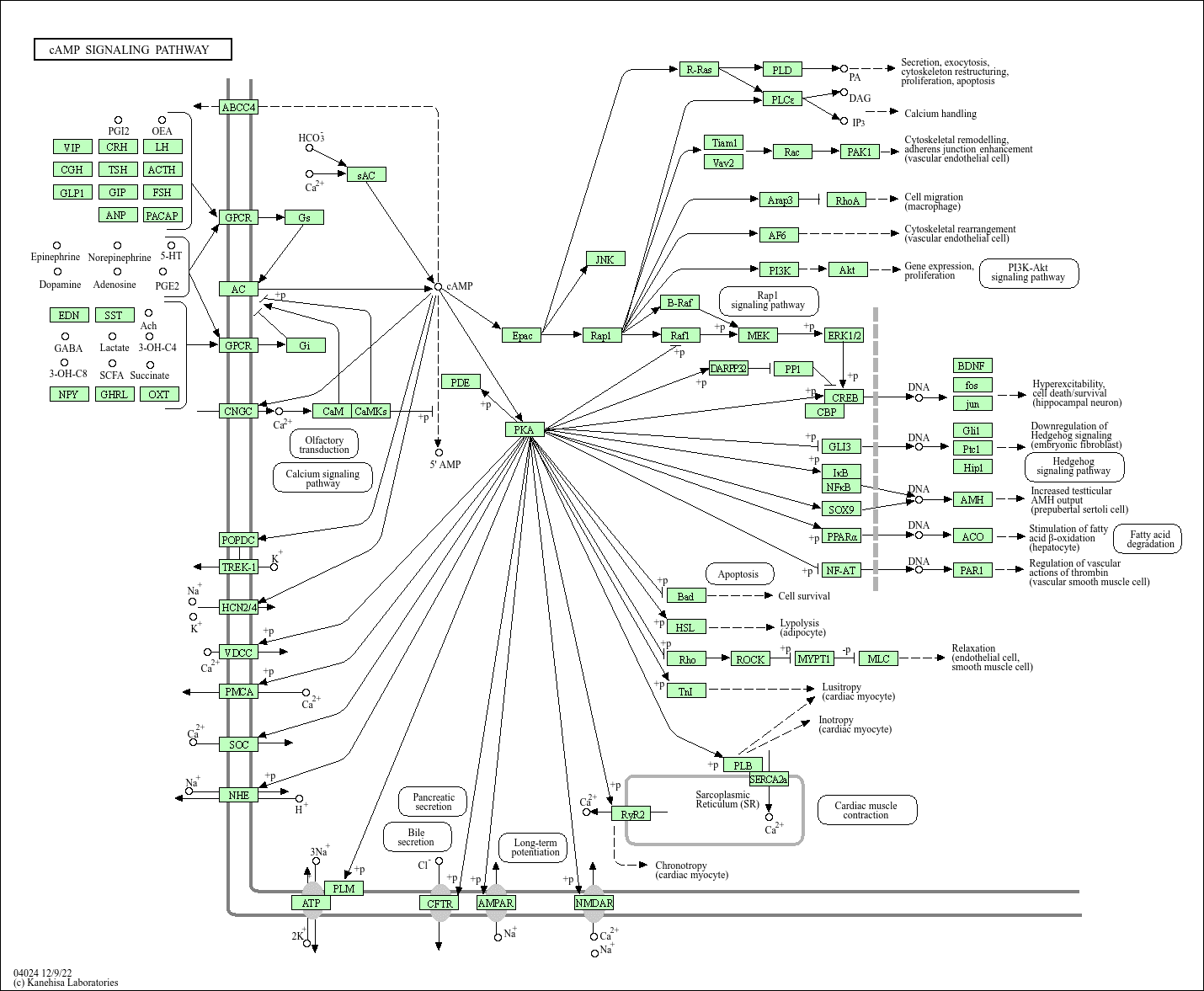

Coming from robotics, coding and engineering, this part of biology always surprised me. In engineering, debugging is iterative, targeted, and most often direct. If a subsystem fails, you can usually tell exactly where and why. You isolate the fault, fix it, and move on. Biology does not offer that luxury. Most of what we call "debugging" in biology is really an elaborate form of trial-and-error wrapped inside an assay. We perturb a cell, edit a sequence, express a construct, and then measure something two or three steps removed from the event we actually care about, usually through a fluorescent reporter or a proxy phenotype. Want to know if a receptor bound its ligand? We don't measure the interaction itself. We measure fluorescence downstream of transcription downstream of signaling downstream of binding. These tools give us estimates, not coordinates. And when a system behaves unexpectedly, there is no equivalent of a fault log or stack trace.

In large-scale induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) engineering projects I worked on, we occasionally saw differentiation drift caused by a weak, unintended interaction. For example, an engineered transcription factor transiently binding a partner outside the target pathway and nudging the timing of a fate decision.

A critique that captured this gap long before CRISPR or AlphaFold existed is Yuri Lazebnik's 2002 essay "Can a Biologist Fix a Radio?" He imagined handing a broken radio to a team of biologists and watching them diagnose it exactly the way we approach cellular systems: disable one component and see which "phenotype" disappears; overexpress another part to check whether the output signal increases; interrupt a suspected connection and monitor whether a downstream reporter changes; interpret fluctuations in a proxy as evidence of causality. Anyone in biotech who has run knockout screens or pathway reporters has lived some version of this workflow. The uncomfortable truth is that this still REALLY is how we investigate what we call "complex systems" when we don't have a wiring diagram. And we build increasingly exquisite, expensive, and elaborate laboratory and software infrastructure around it to make it work.

We've automated everything except the part that actually matters: understanding the interactions that govern the system. Biological data is collected as isolated observations rather than as connected systems. We quantify individual components (proteins, variants, perturbations) while nearly everything we care about emerges from interactions, especially how proteins interact with each other. This is the core wiring of cellular behavior and is still largely unmapped because traditional methods are slow, expensive, and one-dimensional. These interactions define everything from receptor specificity to pathway topology to emergent phenotypes. Two drugs with identical molecular profiles can produce vastly different clinical outcomes because the relevant interaction isn't in the training data. Likewise, an engineered receptor that looks perfect on paper can misfire in cells because of the broader interaction ecosystem or off-target effects invisible to the assay. And critically, the value is not just in knowing each interaction, but in knowing patterns of interaction: families, motifs, cross-reactivities, competition groups, emergent behaviors. Once interactions are measurable, a surprising number of things become simpler: models behave more predictably, assays make more sense, and the "strange outlier" results stop feeling like supernatural events. I'm not claiming this solves drug discovery or magically rewrites textbooks. But it does shift the work from navigating with a half-finished map to navigating with enough structure that course corrections are real.

At some point this stopped feeling like an abstract curiosity and started feeling like a practical engineering problem. If so much of discovery hinges on interactions we can't see, then maybe the solution isn't to build bigger screens or more elaborate reporters, but to measure the interactions directly and at scale, effectively constructing the missing coordinate.

The missing coordinate is an engineering-grade interaction axis built from directly measuring who interacts with whom at proteome scale. And the only way to get it is with a platform that can collide thousands of receptors, variants, and ligands in the same experiment and read out the full pattern of specificity, off-targets, cooperativity, and emergent behavior in one shot. That idea eventually became the motivation behind Lagomics. We're still early, still building, and still discovering the edges of the map. But the goal is to find the missing reference frame so that biologists, computational teams, and drug discovery programs can spend less time guessing and more time reasoning from something solid.

Biology will always surprise us, but it shouldn't do so for reasons we simply forgot to measure. Once interaction data becomes observable at scale, the field can move from reverse-engineering phenotypes to genuinely programmable biology. And when the interaction layer is known, in silico simulation becomes accurate enough that most design-build-test cycles no longer require a full-on multiyear wet lab pipeline in the loop; the lab becomes a validation step rather than the engine of discovery. At that point you don't need billion-dollar programs to produce billion-dollar outcomes, you just need the coordinate we've been missing.